OPEN FARM

(Process Report)

Asian Performing Arts Camp Report (Part 2)

Beyond online: where will the artists go?

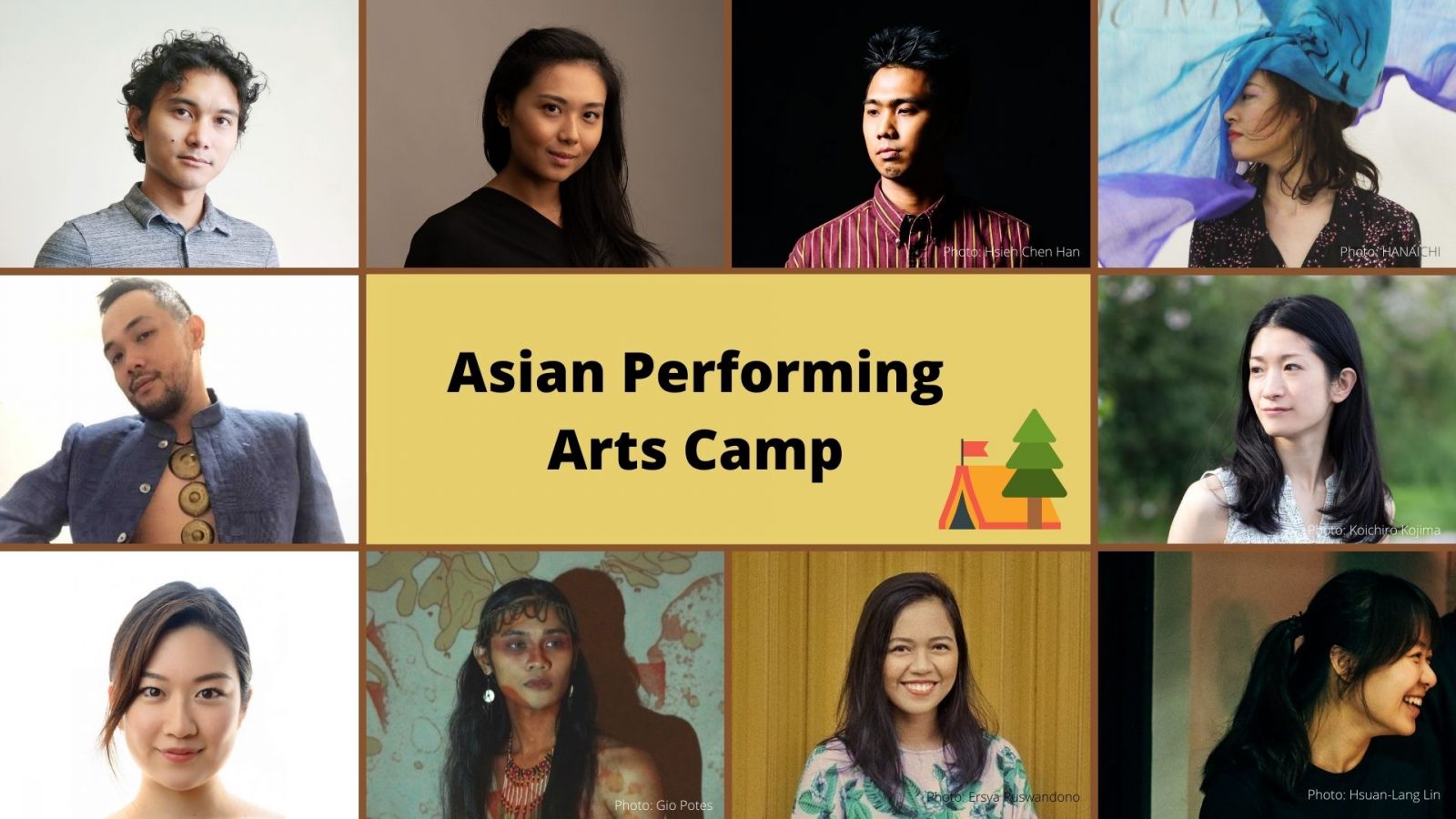

On October 30, the Asian Performing Arts Camp—an online camp for young performing arts practitioners working across Asia to gather and cultivate their practices and fields—gave their final presentations via Zoom after two-months of research.

Text by KAWANO Momoko

Asian Performing Arts Camp Report (Part 1) A midterm presentation showcasing eight artists’ research processes

https://tokyo-festival.jp/2021/en/openfarm_1

In the midterm presentation held a month ago, the eight participants were each given ten minutes to present their research themes and areas of interest in any format they chose. This time, the eight participants were divided into three groups. Taking the “camp” as an overarching concept, facilitator JK Anicoche beamed in with a cozy nature campsite backdrop and, similarly, YAMAGUCHI Keiko joined from her room in mountain-climbing attire, with a self-built tent made out of newspaper.

Referring to each presentation group as a “Bonfire,” the two facilitators opened the session with a greeting: “Prepare your coffee, your blankets, and your open minds and your open hearts as we light some fire and share some human warmth—even here, online.” Amidst the lively atmosphere, a sense of nervous anticipation floated through the screen.

Both participants and audience members acknowledged each other's presence by waving to one another and making enthusiastic sounds. As the atmosphere soon began warming up, JK announced, “Welcome to the camp!” With that, the three bonfires in the video were lit and the final presentations commenced.

Presentation: Bonfire

- Bonfire 1

WANG Hao-Yeh - Changhua (Taiwan) / Berlin (Germany)

Albert GARCIA - Taipei (Taiwan) / Macao

KUSANAGI JuJu - Tokyo (Japan)

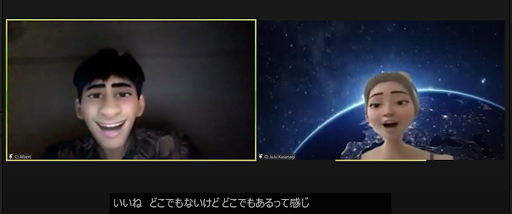

Lively footage reminiscent of a kind of a variety show starts playing. A show hosted by WANG Hao-Yeh and interpreter YAMADA Kyle has started, where they observe people inside their homes. Albert GARCIA and KUSANAGI JuJu are shown relaxing inside their respective abodes, and we spend some time peering into their lives. It appears to be a live-streamed show where the audience members of the presentation send their comments freely through the live chat, to which the two hosts cheerfully respond. After a while, an advertisement appears on the screen: “Anything tastes good with Sriracha Sauce! Delivering to you from the newly opened department store! Only 99 dollars!” It seems that a department store has just been built in this town.

The newly built department store is present both inside and outside the home, showing the complexity of the perceived distance between the individual and the city/town. There is Albert, who cannot return home due to the Covid-19 pandemic, and then there is JuJu, who was born in Australia and raised in Japan. She expressed uncertainty about her sense of belonging, lamenting how her home feels far away, her mother tongue sounds foreign, and she feels different from everyone around her when living in Japan. What is “home”? The two meet in a virtual space and attempt to make a connection, only to disappear from the screen.

The sense of belonging, of identity, of each of the three members of Bonfire 1 is not necessarily tied to their place of origin or current residence: Hao-Yeh feels the loss of home due to the rise of a new department store; Albert is in search of his identity and community as an immigrant; JuJu is interested in how to foster a sense of community when there is a distance in time and space. These individual themes and interests were unified into one presentation. With the ubiquity of the online realm as a public space in the time of Covid, it may be necessary for future generations to reexamine the spaces they inhabit.

- Bonfire 2

Eka WAHYUNI - Yogyakarta (Indonesia)

Albert GARCIA - Taipei (Taiwan) / Macao

Serena MAGILIW - Manila (The Philippines)

In Bonfire 2, a collaboration was formed between the three participants, their research, and the participation of the audience. Eka WAHYUNI, who was pursuing research from the point of view of “how people want to be perceived from the outside,” captured a single person from multiple cameras—a method used by Albert during the midterm presentation.

Albert grew up in a Filipino household but has never lived in the Philippines. Born and raised as a Filipino, Serena teaches Albert—who’s research pursues his sense of belonging as an immigrant—the Panatang Makabayan (Patriotic Oath). While both are “kababayan” (fellow Filipinos, countrymen, or townmates), they do not share the same experiences and views, and eventually they end up in a big fight over the chicken-or-egg question.

Serena has been continuing to explore identity and expression as a queer activist. Here, two of her acquaintances also made an appearance. The audience members were split into the breakout rooms (a feature on Zoom allowing participants to separate into small groups), where research was shared. Finally, everyone exchanged the salutation “tarew!” (which means “true” or “real”) in this collaboration that extended beyond the three named participants. Not only did they relate to each other but, as artists, they showcased the strength in engaging the people around them in the online space.

- Bonfire 3

ANG Xiao Ting - Singapore

Walid ALI - Kuching (Malaysia)

KIKUCHI Monami - Tokyo / Chiba / Yamagata (Japan)

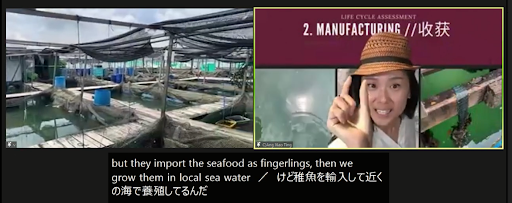

The final bonfire was a joint presentation using common images such as fish and water as a bridge between performances. ANG Xiao Ting—who has undertaken research into the gastronomy of Singapore’s islands, including the treatment of fish—asked questions to make people consider fish in the context of their own immediate surroundings. She asked people to think of their favorite fish dish, and use a related image as their Zoom background, as well as where their fish is sourced from. Then, she took on the role of a worker in a floating fish farm to discuss selling and importing fish, addressing environmental issues including distribution. Through this, she sought to create a new form of lecture performance online.

As with their midterm presentations, both Walid and Monami gave a performance using the body. Individual memories of water as shared between the three artists were used as starting points to build a performance that connects their memories. The participants each used their own means of expression to explore the common themes of water and fish. This allowed them to transcend distance by conjuring shared imagery, while at the same time highlighting their differences.

What was common throughout the Bonfire presentations was the precarity of one’s own existence and place in the world. While faced with movement restrictions during the pandemic, participants are still able to communicate with each other through a common language (English). However, this might make the notion of belonging feel even more ambiguous for most of the participants, whose native tongue is not English. How do the artists—able to transcend distance more than ever through language and online tools—grasp the meaning of place? In connecting with the theme of this year’s Tokyo Festival Farm—“Why Cities?”—this felt like an effort to explore how future artists can live.

Feedback Session

In the second half of the session, Helly MINARTI (Indonesia), curator and founder of LINGKARAN | koreografi, and UEDA Kanayo, who gave a lecture in the program, participated as guests and provided feedback on the presentations. The two offered their thoughts on the three Bonfires and suggested that language, identity, and place were among the common themes. This year also marks the second time that the camp was held online during the coronavirus crisis, and so the excitement of being able to connect with others has passed. Helly’s comment responding to Eka’s final text “Live is ended,” shown at the end of the video, was particularly striking, noting that while the text signaled the end of the Bonfire 2 livestream, it can simultaneously be read as signaling the end of the live-streaming format.

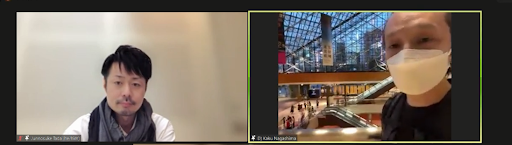

Tokyo Festival Farm Directors TADA Junnosuke and NAGASHIMA Kaku also reflected back on the presentations. Director Nagashima commented, “this was a really successful example of an online presentation.” Showing himself on-screen from the atrium of the Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre, he said, “while I’m here, I think I got to know an alternative reality. I felt a sense of possibility in that we are not just using the online platform to compensate for not being able to gather in-person,” expressing the sense of reality he felt through the screen. Director Tada also felt that the camp had further evolved with its second year online. He appreciated the caring attitudes of the participants, stating that the camp’s development is thanks to the artists’ sense of humor, hospitality, and love. He was encouraged by the thought that this is how human beings have overcome struggles and survived.

Finally, the facilitators Keiko and JK encouraged all of the participants to take their two-month camp research and collaborative work experience forward into their future activities. JK noted that working in the performing arts does not offer a cure-all solution to what is happening in the present, and that similarly this camp does not yield visible results immediately. It is for this reason that a platform is necessary on which to build future steps. The three bonfires built on the individual performances developed in the midterm presentation to create new performances. For people with different backgrounds to create something in a limited amount of time while respecting each other, it is necessary to establish a space where participants feel safe to work. The two-month camp made that possible.

The camp participants have perhaps gained a sense of feeling that they can—even from remote locations—share practices rooted in their identities. There are sure to be new forms of performing arts of the future only possible for young people with that feeling running through their body and soul. To make this possible, it is important for spaces like the camp to continue to exist in the world.

Mr. JK Anicoche, one of the facilitators of Asian Performing Arts Camp, passed away in November after the program was over. We deeply regret the loss and express our sincere condolences to his family and friends.

Asian Performing Arts Camp Final Presentation

https://tokyo-festival.jp/2021/en/program/camp/

[Archive] Available until Sunday 5 December 2021

・Part 1 Presentation

・Part 2 Feedback session

Grant : The Japan Foundation Asia Center Grant Program for Enhancing People-to-People Exchange

KAWANO Momoko

KAWANO Momoko studied theatre and stage production at J. F. Oberlin University. After graduating she worked as a writer and editor for weekly magazines, television, specialist journals, etc. She currently writes interviews and articles on performances of contemporary dance and other fields, with a focus on theatre. As well as continuing to visit theatre festivals in Japan and overseas, in recent years she has been reporting on local culture and accessibility in performing arts.